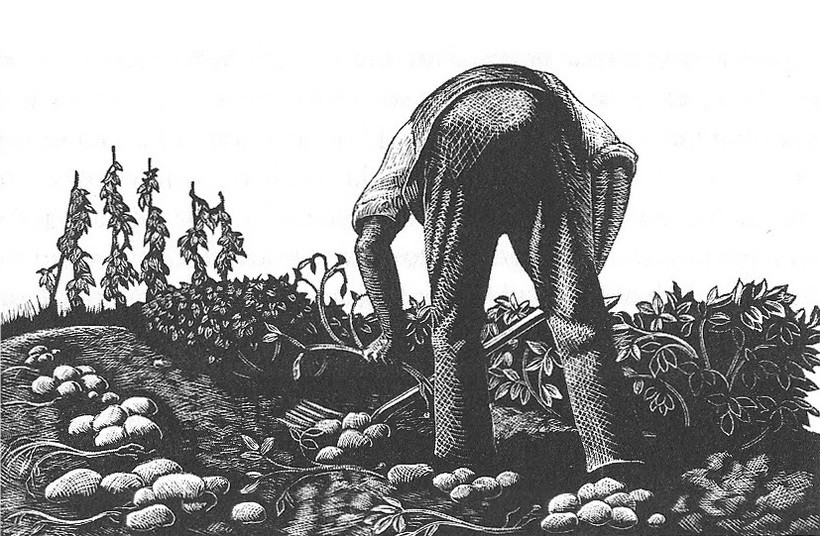

Wood engraving of man digging potatoes. Image: Claire Leighton, courtesy of the artist’s estate

Wood engraving of man digging potatoes. Image: Claire Leighton, courtesy of the artist’s estate

Green Earth Awakening organiser, Rosie Lancaster, shares her thoughts on the concept of ‘indigenous Britain’

Claims of an ‘indigenous Britain’ have been recently hijacked as nationalist slogans by far right campaigners. It can be argued that any idea of a people native to Britain is obsolete, and in current cultural terms; racist. But if we put aside the idea of indigenous as a purely ‘native’ or isolated community then we can use the term to describe a people living in response to their past and in respect to their future. We can start to explore how an indigenous world view could open up into a global, collective vision for our future.

What can be learnt from an indigenous world view? Their stance is a holistic and interconnected understanding of resources and collective impact. All aspects of the environment are considered equal to humans as conscious beings. They believe the world is inherited from our ancestors and what we leave behind affects the next generations. Long term thinking of ‘future ancestors’ is a vital part in recognising our role and responsibility within a massive complex system of life.

Current living standards in the west allow many to benefit from a comfort and ease far removed from a survivalist existence. There has developed a disassociation with the resources and labour required in the meeting of day to day living needs. Resources are therefore depleting and we begin to spiral into blind desire for the status quo while taking more than is sustainable and abusing a cheap human labour force.

Fear is growing as to what the future may look like if current resource consumption is not halted. Younger generations growing up with the looming shadow of climate chaos are experiencing resentment for not only their uncertain inheritance but also their perceived ‘identity’ as a destructive species. Many feel a desperation and hopelessness in the face of so much uncertainty. How does a disillusioned generation empower themselves for the benefit of future world inheritors?

What we can learn from an indigenous world view is to take into account the journey our ancestors have taken. This means recognising the faults along the way but also considering the achievements.What industrialised Britain has done for us is to create a healthy society which has enabled a move beyond ‘survival values.’ Christian Welzel’s writes in Freedom Rising:

[…] fading existential pressures [i.e., threats and challenges to survival] open people’s minds, making them prioritize freedom over security, autonomy over authority, diversity over uniformity, and creativity over discipline. By the same token, persistent existential pressures keep people’s minds closed, in which case they emphasize the opposite priorities…the existentially relieved state of mind is the source of tolerance and solidarity beyond one’s in-group; the existentially stressed state of mind is the source of discrimination and hostility against out-groups.

We currently live in a culture of global horizons; influenced by ideas and products from every corner of the world. This diverse multiculture creates the potential for a harmonious, holistic world view. Ironically globalism can instill an individualist mentality that builds separation between cultures and even the natural environment. How do we hold a collective idealism that incorporates all of the human and non human world?

In light of Britain’s EU referendum and America’s Trump, there is a current political trend towards an anti-globalisation and a defence of national identities. There is a desire to move away from global individualism and focus on the local. What separates Trump’s brand of national identity from, for example, the Standing Rock Sioux in their defence of Native American Land against oil development; is an awareness that the nature they defend is inseparable from their cultural heritage. For Trump, it could be assumed that based on recent decisions made in his environmental policy, nature is an obstacle to bypass.

We may be beyond the point of distinguishing ancestoral lineage within our current diverse culture, but we can recognise the history of a place and the journey of the people that have populated it.The folklore and traditions that have come before us may tell us vital information about how to interact holistically with our landscape. This awareness of ancestors, whether of blood or not, globally or locally, create a narrative that will continue through future generations. This sense of identity gives purpose and responsibility for the stories we leave behind.

If we are to move collectively towards a more harmonious interaction with our natural resources, we have plenty to learn from the methods of indigenous cultures. The current political move towards anti -globalisation is playing out the desires for tribal community. However, we must be careful in harnessing these desires in relationship to the wider context of our ecological heritage. Without a connection to the human and non human world, we are in danger of being consumerist individualists masquerading as global community members. We cannot understand the true sense of interconnection without recognising ourselves as part of, not adjacent to the natural world. The journey towards this understanding must incorporate all aspects of what we are and from where we have come.